One of the challenges in writing programs in today’s RIA environments (Javascript, Flex, Silverlight and GWT) is expressing the flow of control between multiple asynchronous XHR calls. A “one-click-one-XHR” policy is often best, but you don’t always have control over your client-server protocols. A program that’s simple to read as a synchronous program can become a tangle of subroutines when it’s broken up into a number of callback functions. One answer is program translation: to manually or automatically convert a synchronous program into an asynchronous program: starting from the theoretical foundation, this article talks about a few ways of doing that.

Thibaud Lopez Schneider sent me a link to an interesting paper he wrote, titled “Writing Effective Asynchronous XmlHttpRequests.” He presents an informal proof that you can take a program that uses synchronous function calls and common control structures such as if-else and do-while, and transform it a program that calls the functions asynchronously. In simple language, it gives a blueprint for implementing arbitrary control flow in code that uses asynchronous XmlHttpRequests.

In this article, I work a simple example from Thibaud’s paper and talk about four software tools that automated the conversion of conventional control flows to asynchronous programming. One tool, the Windows Workflow Foundation, lets us compose long-running applications out of a collection of asynchronous Activity objects. Another two tools are jwacs and Narrative Javascript, open-source translators that translated pseudo-blocking programs in a modified dialect of JavaScript into an asynchronous program in ordinary JavaScript that runs in your browser.

A simple example: Sequential Execution

I’m going to lift a simple example from Thibaud’s paper, the case of sequential execution. Imagine that we want to write a function f(), that follows the following logic

[01] function f() {

[02] ... pre-processing ...

[03] result1=MakeRequest1(argument1);

[04] ... think about result1 ...

[05] result2=MakeRequest2(argument2);

[06] ... think about result2 ...

[07] result3=MakeRequest3(argument3);

[08] ... think about result3 ...

[09] return finalResult;

[10] }

where functions of the form MakeRequestN are ordinary synchronous functions. If, however, we were working in an environment like JavaScript, GWT, Flex, or Silverlight, server requests are asynchronous, so we’ve only got functions like:

[11] function BeginMakeRequestN(argument1, callbackFunction);

It’s no longer possible to express a sequence of related requests as a single function, instead we need to transform f() into a series of functions, like so

[12] function f(callbackFunction) {

[13] ... pre-processing ...

[14] BeginMakeRequest1(argument,f1);

[15] }

[16]

[17] function f1(result1) {

[18] ... think about result1 ...

[19] BeginMakeRequest2(argument2,f2);

[20] }

[21]

[22] function f2(result2) {

[23] ... think about result2 ...

[24] BeginMakeRequest3(argument3,f3);

[25] }

[26]

[27] function f3(result3) {

[28] ... think about result 3 ...

[29] callbackFunction(finalResult);

[30] }

My example differs from the example of on page 19 of Thibaud’s paper in a few ways… In particular, I’ve added the callbackFunction that f() uses to “return” a result to the program that calls it. Here the callbackFunction lives in a scope that’s shared by all of the fN functions, so it’s available in f3. I’ve found that when you’re applying Thibuad’s kind of thinking, it’s useful for f() to correspond to an object, of which the fN() functions are methods. [1] [2] [3]

Thibaud also works the implementation of if-then-else, switch, for, do-while, parallel-do and other common patterns — read his paper!

What next?

There are things missing from Thibaud’s current draft: for instance, he doesn’t consider how to implement exception handling in asynchronous applications, although it’s quite possible to do.

Thinking about things systematically helps you do things by hand, but it really comes into it’s own when we use systematic thinking to develop tools. I can imagine two kinds of tools based on Thibaud’s ideas:

- Specialized languages for expressing asynchronous flows, and

- Compilers that transform synchronous programs to asynchronous programs

Windows Workflow Foundation

Windows Workflow Foundation is an example of the first approach.

Although it’s not designed for use in asynchronous RIA’s, Microsoft’s Windows Workflow Foundation is an new approach to writing reactive programs. Unfortunately, like a lot of enterprise technologies, WWF is surrounded by a lot of hype that obscures a number of worthwhile ideas: the book Essential Windows Workflow Foundation by Shukla and Schmidt is a lucid explanation of the principles behind it. It’s good reading even if you hate Microsoft and would never use a Microsoft product, because it could inspire you to implement something similar in your favorite environment. (I know someone who’s writing a webcrawler in PHP based on a similar approach)

What does it do?

In WWF, you create an asynchronous program by composing a set of asynchronous Activities. Ultimately your program is a tree of Activity objects that you can assemble any way you like, but typically you’d build them with a XAML (XML) file that might look like

[31] <Interleave x:Name="i1">

[32] <Sequence x:Name="s1">

[33] <ReadLine x:Name="r1" />

[34] <WriteLine x:Name="w1"

[35] Text="{wf:ActivityBind r1,path=Text}" />

[36] <ReadLine x:Name="r2" />

[37] <WriteLine x:Name="w2"

[38] Text="{wf:ActivityBind r2,path=Text}" />

[39] </Sequence>

[40] <Sequence x:Name="s2">

[41] <ReadLine x:Name="r3" />

[42] <WriteLine x:Name="w3"

[43] Text="{wf:ActivityBind r3,path=Text}" />

[44] <ReadLine x:Name="r4" />

[45] <WriteLine x:Name="w4"

[46] Text="{wf:ActivityBind r4,path=Text}" />

[47] </Sequence>

[48] </Interleave>

(The above example is based on Listing 3.18 on Page 98 of Shukla and Schmidt, with some namespace declarations removed for clarity)

This defines a flow of execution that looks like:

The <Interleave> activity causes two <Sequence> activities to run simultaneously. Each <Sequence>, in turn, sequentially executes two alternating pairs of <ReadLine> and <WriteLine> activities. Note that the attribute values that look like {wf: ActivityBind r3,path=Text} wire out the output of a <ReadLine> activity to the input of a <WriteLine> activity.

Note that <Interleave>, <Sequence>, <ReadLine> and <WriteLine> are all asynchronous activities defined by classes Interleave, Sequence, ReadLine And WriteLine that all implement Activity. An activity can invoke other activities, so it’s possible to create new control structures. Activities can wait for things to happen in the outside world (such as a web request or an email message) by listening to a queue. WWF also defines an elaborate model for error handling.

Although other uses are possible, WWF is intended for the implementation of server applications implementations that implement workflows. Imagine, for instance, a college applications system, which must wait for a number of forms from the outside, such as

- an application,

- standardized test scores, and

- letters of reccomendation

and that needs to solicit internal input from

- an initial screening committee,

- the faculty of individual departments, and

- the development office.

The state of a workflow can be serialized to a database, so the workflow can be something that takes place over a long time, such as months or weeks — multiple instances of the workflow can exist at the same time.

WWF looks like a fun environment to program for, but I don’t know if I’d trust it for a real business application. Why? I’ve been building this sort of application for years using relational databases, I know that it’s possible to handle the maintenance situations that occur in real life with a relational representation: both the little tweaks you need to make to a production system from time to time, and the more major changes required when your process changes. Systems based on object serialization, such as WWF, tend to have trouble when you need to change the definition of objects over time.

I can say, however, that the Shukla and Schmidt book is so clear that an ambitious programmer could understand enough of the ideas behind WWF to develop a similar framework that’s specialized for developing asynchronous RIAs in Javascript, Java, or C# pretty quickly. Read it!

Transforming Javascript and Other Languages

Another line of attack on asynchronous programming is the creation of compilers and translators that transform a synchronous program into a synchronous program. This is particularly popular in Javascript, where open-source tools such as jwacs (Javascript With Advanced Continuation Syntax) let you write code like this:

[49] function main() {

[50] document.getElementById('contentDiv').innerHTML =

[51] '<pre>'

[52] + JwacsLib.fetchData('GET', 'dataRows.txt')

[53] + '</pre>';

[54] }

Jwacs adds four new keywords to the Javascript language: internally, it applies transformations like the ones in the Thibaud paper. Although it looks as if the call to JwacsLib.fetchData blocks, in reality, it splits the main() function into two halves, executing the function by a form of cooperative multitasking.

Narrative Javascript is a similar open-source translator that adds ->, a “yielding” operator to Javascript. This signals the translator to split the enclosing function, and works for timer and UI event callbacks as well as XHR. Therefore, it’s possible to write a pseudo-blocking sleep() function like:

[55] function sleep(millis) {

[56] var notifier = new EventNotifier();

[57] setTimeout(notifier, millis);

[58] notifier.wait->();

[59] }

Narrative Javascript doesn’t remember the special nature of the the sleep() function, so you need to call it with the yielding operator too. With it, you can animate an element like so:

[60] for (var i = 0; i < frameCount - 1; i++) {

[61] var nextValue = startValue + (jumpSize * i);

[62] element.style[property] = nextValue + "px";

[63] sleep->(frequency);

[64] }

You can use the yielding operator to wait on user interface events as well. If you first define

[65] function waitForClick(element) {

[66] var notifier = new EventNotifier();

[67] element.onclick = notifier;

[68] notifier.wait->();

[69] }

you can call it with the yielding operator to wait for a button press

[70] theButton.innerHTML = "go right"; [71] waitForClick->(theButton); [72] theButton.innerHTML = "-->"; [73] ... continue animation ...

The RIFE Continuation Engine implements something quite similar in Java, but it translates at the bytecode level instead of at the source code level: it aims to transform the server-side of web applications, rather than the client, by allowing the execution of a function to span two separate http requests.

Conclusion

It’s possible to systematically transform a function that’s written in terms of conventional control structures and synchronous function calls into a collection of functions that performs the same logic using asynchronous function calls. A paper by Thibaud Lopez Schneider points the way, and is immediately useful for RIA programmers that need to convert conventional control structures in their head into asynchronous code.

A longer-term strategy is to develop frameworks and languages that make it easier to express desired control flows for asynchronous program. The Windows Workflow Foundation from Microsoft is a fascinating attempt to create a specialized language for assembling asynchronous programs from a collection of Activity objects. jwacs and Narrative Javascript are bold attempts to extend the Javascript language so that people can express asynchronous logic as pseudo-threaded programs. The RIFE Continuation Engine demonstrates that this kind of behavior can be implemented in more static languages such as Java and C#. Although none of these tools are ready for production-quality RIA work, they may lead to something useful in the next few years.

]]>Many people have independely discovered a new design pattern, the “Multiton”, which, like the “Singleton” is an initialization pattern in the style of the Design Patterns book. Like the Singleton, the Multiton provides a method that controls the construction of a class: instead of maintaining a single copy of an object in an address space, the Multiton maintains a Dictionary that maps keys to unique objects.

The Multiton pattern can be used in systems that store persistent data in a back-end store, such as a relational databases. The Multiton pattern can be used to maintain a set of objects are mapped to objects (rows) in a persistent store: it applies obviously to object-relational mapping systems, and is also useful in asynchronous RIA’s, which need to keep track of user interface elements that are interested in information from the server.

An alternate use case of Mulitons, seen in the “Multicore” version of the PureMVC framework, is the extension of the Singleton pattern to support multiple instances of a system in a single address space.

As useful as the Multiton pattern is, this article explains how Multitons use references in a way that doesn’t work well with conventional garbage collection. Multitons are a great choice when the number of Multitons is small, but they may leak memory unacceptablely when more than a few thousand are created. Future posts will describe patterns, such as the Captive Multiton, that provide the same capabilities with more scalable memory management — subscribe to our RSS feed to keep informed.

Use of a Multiton in An Asynchronous Application

In our last article on Model-View Separation in Asynchronous RIA’s, we used a Singleton object that represented an entire table in a relational database. This object maintained a list of listerners that were interested in the contents of a table. In this case, the amount of information in the table was small, and often used in the aggregate, so retreiving a complete copy of the table was a reasonable level of granularity. We could imagine a situation, however, where the number of records and size of the records is enough that we need to transfer records individually. (This specific case is an outline of an implementation for Silverlight: a GWT implementation would be similar — details specific to GWT are talked about in a previous post.)

Imagine, for instance, a BlogPosting object, which represents a post in a blog, which in turn has an integer primary key. The BlogPosting object is a multiton, so you’d write

[01] var posting=BlogPosting.GetInstance(postId);

to get the instance of BlogPosting that corresponds to postId. Client objects can’t really write something like

[02] TitleField.Text=posting.Title

because the operation of retrieving text from an the server is asynchronous, and won’t return in time to return a value, either on line [01] or [02]. More reasonably, a BlogPostingViewer can register itself against a BlogPosting instance so it will be notified when information is available about the blog posting.

[03] public class BlogPostingViewer: UserControl,IBlogPostingListener {

[04] protected int PostId;

[05]

[06] public BlogPostViewer(int postId) {

[07] PostId=postId;

[08] BlogPosting.GetInstance(postId).AddListener(this);

[09] }

[10]

[11] public void Dispose() {

[12] BlogPosting.GetInstance(postId).RemoveListener(this);

[13] super.Dispose();

[14] }

This example shows a pattern usable in a Silverlight applicaton, unlike the GWT style in the model-view article. The Dispose() method will need to be called manually when the BlogPostingViewer is no longer needed, since it will never be garbage collected so long as a reference to it inside the BlogPosting exists. (This points to a general risk of memory leaks with Multitons that we’ll talk about later.) This problem can be addre

The BlogPostingViewer goes on to implement the IBlogPostingListener interface, updating the visual appearance of the user interface to reflect information from the UI:

[15] public void UpdatePosting(BlogPostingData d) {

[16] if (d==null) {

[17] ClearUserInterface(); // user-defined method blanks out UI

[18] return

[19] }

[20] TitleField.Text=d.Title;

[21] ...

[22] }

}

We assume that BlogPostingData represents the state of the BlogPosting at a moment in time, distinct from the BlogPosting, which represents the BlogPosting as a persistent object. BlogPostingData might (roughly) correspond to the the columns of a relational table and look something like:

[23] public class BlogPostingData {

[24] public string Title { get; set;}

[25] public Contributor Author { get; set; }

[26] public string Body { get; set;}

[27] public Category[] AssociatedCategories { get; set;}

[28] ...

[29] }

We could then add a BlogPostingViewer to the user interface and schedule it’s initialization by writing

[30] var viewer=new BlogPostingViewer(PostId); [31] OuterControl.Children.Add(viewer); [32] BlogPosting.GetInstance(PostId).Fetch();

Note that line [32] tells the BlogPosting instance to retreive a copy of the posting from the server (an instance of BlogPostingData) and call UpdatePosting() on all of the listeners. Therefore, there will be a time between line [30] and the time when the async call started on line [32] gets back when the BlogPostingViewer is empty (not initialized with BlogPostingData.) Therfore, the BlogPostingViewer must be designed so that nothing bad happens when it’s in that state: it has to show something reasonable to user and not crash the app if the user clicks a button that isn’t ready yet.

(In a more developed application, the BlogPosting could keep a cache of the latest BlogPostingData: this could improve responsiveness by updating the BlogPostingViewer at the moment it registers, or by doing a timestamp or checksum stamp against the server to reduce the bandwidth requirements of a Fetch(), just watch out for the unintended consequences of multiple code paths.)

Implementing a Muliton

Here’s an implementation of a Multiton in C# that’s not too different from the Java implementation from Wikipedia.

class BlogPosting {

#region Initialization

private static readonly Dictionary<int,BlogPosting> _Instances =

new Dictionary<int,BlogPosting>();

private BlogPosting(int key) {

... construct the object ...

}

public static BlogPosting GetInstance(int key) {

lock(_Instances) {

BlogPosting instance;

if (_Instances.TryGetValue(key,out instance)) {

return instance;

}

instance = new BlogPosting(key);

_Instances.Add(key, instance);

return instance;

}

}

#endregion

... the rest of the class ...

}

I’m pretty sure that a version of this could be created in C# with slightly sweeter syntax that would look like

BlogPosting.Instance[postId]

but this doesn’t address the weak implementation of static inheritence in many popular languages that requires us to cut-and-paste roughly 20 lines of code for each Multiton class, rather than being able to reuse inheritence logic. The Ruby Applications Library, on the other hand, contains a Multiton class that can be used to bolt Multiton behavior onto a class. It would be interesting to see what could be accomplished with PHP 5.3′s late static binding.

Multitons And Memory Leaks

Multitons, unfortunately, don’t interact well with garbage collectors. Once a Multiton is created, the static _Instances array will maintain a reference to every Multiton in the system, so that Multitons won’t be collected, even if no active references exist.

You might think you could manually remove Multitons from the _Instances list, but this won’t be entirely reliable. In the case above, each BlogPosting maintains a list of IBlogPostingListeners. You could, in principle, scavenge BlogPostings with an empty set of listerners, but that doesn’t stop a class from squirreling away a copy of a BlogPosting that will later conflict with a new BlogPosting that somebody creates by using BlogPosting.GetInstance().

WeakReferences, as available in dot-Net and the full Java platform (as opposed to GWT), are not an answer to this problem, because references work backwards in this case: a BlogPosting is collectable if (i) no references to the BlogPosting exist outside the _Instances array, and (ii) a BlogPosting doesn’t hold references to other objects that may need to be updated in the future.

The severity of this issue depends on the number of Multitons created and the size of the Mulitons. If the granularity of Multitons is coarse, and you’ll only create five of them, there’s no problem. 1000 Multitons that each consume 1 kilobyte will consume about a megabyte of RAM, which is inconsequential for most applications these days. However, this amounts to a scaling issue: an application that works fine when it creates 50 Mulitons could break down when it creates 50,000.

One answer to this problem is to restrict access to Muliton so that: (i) references to Multitons can’t be saved by arbitrary objects and (ii) manages Multitons with a kind of reversed reference count, so that Multitons are discared when they no longer hold useful informaton. I call this a Captive Multiton, and this will be the subject of our next exciting episode: subscribe to our RSS feed so you won’t miss it.

More Information About Multitons

So far as I can tell, Multitons have been independently discovered by many developers in recent years. I used Multitons (I called them “Parameterized Singleons”) in the manner above in a GWT application that I developed in summer 2007. The PureMVC Framework uses Multitons to allow multiple instances of the framework to exist in an address space. A reusable Multiton implementation exists in Ruby.

Conclusion

The Muliton Pattern is an initialization pattern in the sense defined in the notorious “Design Patterns” Book. Mulitons are like Singletons in that they use static methods to control access to a private constructor, but instead of maintaining a single copy of an object in an address space, a Multiton maintains a mapping from key values to objects. A number of uses are emerging for mulitons: (i) Multitons are useful when we want to use something like the Singleton pattern, but support multiple named instances of a system in an an address space and (ii) Multitons can be a useful representation of an object in a persistent store, such as a relational database. Multitons, however, are not collected properly by conventional garbage collectors: this is harmless for applications that create a small number of mulitons, but poses a scaling problem when Multitons are used to represent a large number of objects of fine granularity — a future posting will introduce a Captive Multiton that solves this problem: subscribe to our RSS feed to follow this developing story.

]]>When people start developing RIA’s in environments such as Silverlight, GWT, Flex and plain JavaScript, they often write asynchronous communication callbacks in an unstructured manner, putting them wherever is convenient — often in an instance member of a user interface component (Silverlight and GWT) or in a closure or global function (JavaScript.)

Several problems almost invariably occur as applications become more complex that force the development of an architecture that decouples communication event handlers from the user interface: a straightforward solution is to create a model layer that’s responsible for notifying interested user interface components about data updates.

This article uses a simple example application to show how a first-generation approach to data updates breaks down and how introducing a model-view split makes for a reliable and maintainable application.

(This is one of a series of articles on RIA architecture: subscribe to the Gen5 RSS feed for future installments.)

Example Application: Blogging And The Category Dropdown

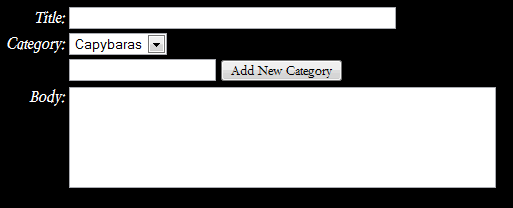

Imagine a blogging application that works like the WordPress blog used on this site. This application consists of a number of forms, one of which is used to write a new post:

This form lets you fill out two text fields: a title and the body of the post. It also contains a dropdown list of categories, and gives you the option of adding a new category. Categories are represented (server-side) in a table in a relational database that looks like:

[01] CREATE TABLE categoryList ( [02] id integer primary key auto_increment, [03] name varchar(255) [04] );

Adding a category to the database requires a call to the server that adds a row to the database and returns the new category list, which is then used to update the dropdown list. I’ll show you samples of the app in a pseudocode in an imaginary environment which combines the best of Silverlight and GWT. First we initialize the form and set an event handler that’s called when somebody clicks on the AddCategoryButton:

[05] class CreatePostForm {

[06] protected TextBox Title;

[07] protected ListBox Category;

[08] protected TextBox AddCategoryName;

[09] protected Button AddCategoryButton;

[10] protected RichTextArea Body;

[11] protected Button Submit;

[12]

[13] public CreatePostForm() {

[14] ... initialize and lay out UI elements ...

[15]

[16] AddCategoryButton.OnClick += AddCategoryButton_OnClick;

[17]

[18] ... finish construction ...

[19] }

Leaving out error handling and other details, the job of the event handler is to pass the name of the new category to the server. The event handler is defined as an instance method of CreatePostForm:

[20] protected void AddCategoryButton_OnClick {

[21] Server.Instance.AddCategory(AddCategoryName.Text,AddCategory_Completed)

[22] }

The AddCategory RPC call is defined on a Singleton called Server, and takes two arguments: (1) a string with the name of the new category, and (2) a reference to to the callback function that gets called when the RPC call is complete. The callback, AddCategory_Completed, is also an instance method:

[23] protected void AddCategory_Completed(List<ListBoxItem> items) {

[24] Category.Items = items;

[25] }

ListBoxItem is a class that represents a single row in a ListBox, which has properties ListBox.Id and ListBox.Name. This is simple and straightforward code, and it ought to maintainable, right?

Let’s see

The Naive Implementation Adapts

Well, when we finish writing the class, we notice the first problem – a minor problem. There are two buttons on the form, so we need two event handlers and two callback functions. As a UI class gets complicated, it can accumulate quite a few callback functions, and it can get tricky keeping track of them all. Careful naming, code organization, and the use of #region in C# can help organize the code, but it’s easy to build UI controls that have tens of methods in which we can get lost.

Over time, we’ll add more forms to the app, and pretty soon we’ll add another form that has a category list: perhaps this a form used by administrators to search for posts: let’s call it AdminSearchForm. AdminSearchForm also contains a Listbox called Category. It’s a protected field of AdminSearchForm, but we need to update it when the administrator adds a new category. It seems reasonable to add a public method to AdminSearchForm

[26] public class AdminSearchForm {

[27] ...

[28] protected ListBox Categories;

[29] ...

[30] public void UpdateCategoryList(List<ListBoxItem> items) {

[31] Categories.Items=items;

[32] }

[33] }

Now we update the AddCategory_Completed function so it updates the AdminSearchForm:

[34] public class CreatePostForm {

[35] ...

[36] protected void AddCategory_Completed(List<ListBoxItems> items) {

[37] Categories.Items=items;

[38] App.Instance.MainTabPanel.AdminSearchForm.UpdateCategoryList(items);

[39] }

[40] }

Not too bad, eh? just four more lines of transparent code to update AdminSearchForm, even if line [38] has a rather ugly coupling to the detailed structure of the application.

The Naive Implementation Breaks Down

Over the next few weeks, we add a few more dropdown lists to the application, we keep doing the same thing, and it’s fine for a while. Then we start running into problems:

- We can’t reuse CreatePostForm to make different versions of the application, because it contains a hard-coded list of all the dropdown lists in the application.

- We can’t update the contents of a category list that it’s a dynamically generated UI element, such as a dialog box, a draggable representation of an item, a search result listing, or an application plug-in.

- You need to consider how all of these dropdown lists get initialized when the application starts (something this code sample doesn’t show.)

- At some point you need to add a second way that a user can add a category (for instance, the “Manage Categories” screen in WordPress) — at that point you can (a) duplicate the code in AddCategory_Completed (bad idea!), (b) have the ManageCategoriesForm class call the AddCategory_Completed method of CreatePostForm (better) or (c) move CreatePostForm someplace else. (best)

- If UI components were responsible for communicating with the server to update themselves, performance could be destroyed by unnecessary communications, with no guarantee that UI components would be updated consistently.

I’m sorry to admit that, when I built my first GWT app, I ran into all of the above problems, plus a number of others. I tried a number of ad hoc solutions until I was forced to sit down and develop an architecture (the one below) that doesn’t run out of steam. Today, you can do better.

Separating the Model And The View

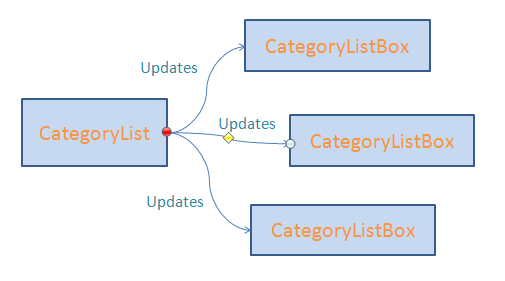

Ok, the plan is to create two classes: CategoryList and CategoryListBox that work together to solve the problem of updating CategoryList boxes. CategoryList is a singleton: it keeps track of the current state of the category list and keeps a list of clients that need to know when the list is updated.

The code for CategoryList looks like:

[41] public class CategoryList {

[42] private static CategoryList _Instance;

[43] public static CategoryList Instance {

[44] get {

[45] if (_Instance==null)

[46] _Instance=new CategoryList();

[47]

[48] return _Instance;

[49] }

[50] }

[51]

[52] private List<ListBoxItems> Items {get; set;}

[53] private List<ICategoryListener> Listeners;

[54] private CategoryList() { ... construct ...};

Java programmers might notice a few C#-isms here, in particular the way the class defines a static property called Instance that other classes use. We don’t, however, use the C# event mechanism, because it doesn’t do exactly what we want to do.

We call UpdateItems when there’s a change in the category list, or when we initialize the category list when the application starts. UpdateItems as an ordinary method, although a C# stylist might probably make the Items property public and put the following logic in the setter:

[55] public void UpdateItems(List<ListBoxItems> items) {

[56] Items=items;

[57] foreach(var l in Listeners) {

[58] l.UpdateItems(Items);

[59] }

[60] }

CategoryListBoxes will register and unregister themselves with the CategoryList with the following methods:

[61] public AddListener(ICategoryListener l) {

[62] Listeners.Add(l);

[63] l.UpdateItems(Items);

[64] }

[65] public RemoveListener(ICategoryListener l) {

[66] Listeners.Remove(l);

[67] }

[68] }

Note that we could have built all of this logic into the CategoryListBox, but by introducing the CategoryList class and the ICategoryListener interface, we’ve decoupled the model from the view, and given ourselves the option to create new visual representations of the category list. (WordPress, for instance has a distinct representation of the category list on the “Manage Category” screens and more than one way you can show a category list to your viewers.)

An interesting point is that AddListener immediately updates the listener when it registers itself. This is a pattern that handles asynchronous initialization: so long as the Items property starts out as something harmless, ICategoryListeners formed before app initialization is completed will be initialized when the application initialization code calls UpdateItems. If an ICategoryListener is created later, it gets initialized upon registration — either way you’re covered without having to think about it.

Let’s take a look at the CategoryListBox, which extends ListBox and implements ICategoryListener.

[70] public CategoryListBox: ListBox, ICategoryListener {

It implements ICategoryListener by implementing the UpdateItems method:

[71] public UpdateItems(List<ListBoxItems> items) {

[72] Items=items

[73] }

We’re going to implement registration and deregistration GWT style, because GWT has particularly strict requirements for how we can access UI components. We’re only allowed to manipulate UI components that are attached to the underyling HTML document tree — by registering and deregistering when the component is attached and detached, components get updated at the proper times:

[74] public OnAttach() {

[75] super.OnAttach();

[76] CategoryList.Instance.AddListener(this);

[77] }

[78]

[79] public OnDetach() {

[80] CategoryList.Instance.RemoveListner(this);

[81] super.OnDetach();

[82] }

The GWT style is particularly nice in that it prevents long-lasting circular references between the view and the model: once you remove the view from the visual, the reference in the model goes away. Silverlight is more forgiving in where you can register the control: you can do it either the constructor or the Loaded event, but I don’t see an equivalent Unloaded event which could be used for automatic deregistration — manual deregistration may be necessary to prevent memory leaks.

So what have we got?

We’ve got a CategoryListBox control that works together with the CategoryList singleton to keep itself updated. So long as we call CategoryList.UpdateItems() during the initialization process, we can just include a CategoryListBox where we want it and never worry about initialization or updating. We can even create new ICategoryListeners if we want to make other visual controls that display the category list. This is a path to simple and scalable development.

What happened to the “Controller?”

The Model-View-Controller paradigm is a perennially popular buzzword in computing. The phrase was coined in the early 1980′s to describe a particular implementation in Smalltalk, which was one of the first implementations of a modern GUI. The Controller is a third component that mediates between the View, Controller and their environment. Although Controllers are widspread in server-based web applications, the Controller often withers away in today’s GUI environments, because it’s functions are often implemented by the event-handling mechanisms that come with the environment. In this case, “Controller”-like logic is embedded in certain methods of the CategoryList.

Note that there are two objects here that could be called a “Model”. I’m calling the CategoryList a model because it has a 1-1 relationship with an object on the server: the categoryList table. CategoryList is a relatively persistent object that lasts for the lifetime of the RIA. There’s another kind of “Model” object, the List<ListBoxItems> that is stored in the Items property of CategoryList and is passed to a ICategoryListener during initialization or update — that object represents the state of the categoryList table at a particular instance time. The generic List<> is an adequate representation of the state of categoryList, although there are many cases where we might want to define a new class to represent the momentary state of a server object.

Something else funny about CategoryList is that it doesn’t export a public Items property. It certainly could, bu I chose not to because a getter for an asynchronous model object is making an empty promise.

A getter in a synchronous application can always initialize or update itself before returning: a similar method in an asynchronous object must return to it’s caller before it can receive information from the server. As asynchronous model can return a cached value of Items if available, but it can make a much firmer promise to deliver correct updates of Items when they become available. CategoryList does, however, deliver a cached copy of Items to CategoryListeners after registration, as this is an effective and efficient mechanism for initialization.

Would it be possible to define only a temporary ‘model’ class and put a single Controller class in charge of updates? Sure. I think that would make more sense in a dynamically typed language like Javascript than it does in Java or C#, since it would be hard for such a Controller to enforce type-safety. Could we call CategoryList a Controller? Perhaps, but I think CategoryList is a logical place to locate methods that manipulate the categoryList — it really is a representation of a persistent object.

What next?

This is a good start, but we haven’t entirely solved the RIA architecture problem. Let’s talk about some of the issues we’d face if we generalized this approach:

- What if there was more than one type of dropdown list? We ought to have an inheritance hierarchy from which we can derive multiple types of dropdown lists. This could include mutable lists such as ContributorTypeListBox as well as immutable lists such as USStateListBox.

- There is just one CategoryList in the application: in some sense it’s globally scoped. What if we want to represent a BlogPost or a Contributor? Simple, use a Multiton instead of a Singleton. Rather than writing CategoryList.Instance, you might write BlogPost.Instance[25], where 25 is the primary key of the blog post. The logic behind Instance[] is responsible for maintaining one and only one instance of BlogPost per actual blog post.

- Isn’t the updating logic in the CategoryList and CategoryListBox repetitive? It is. A mature framework will either push this logic up into superclasses (kind of an embedded controller), or push it out into a Controller. The best approach will depend on the characteristics of the environment and the application.

I’ll be elaborating on these issues in future postings: subscribe to my RSS feed to keep up to date!

Conclusion

It’s simple to initialize and update data in the simplest RIA’s, but asynchronous communications makes it increasingly difficult as applications grow in complexity. A simple approach to data updating that is reliable and maintainable is to create a set of persistent model classes that maintain:

- A cache of the latest data value, and

- A list of dependent view objects

Model objects are responsible for updating View objects, which in turn, are responsible for registering themselves with the Model. The result of this is that View objects can be used composably in the UI: View objects can be added to the user interface without explicitly writing code to manage data updates.

Although this pattern can be applied immediately, we’ll get the most of it when it (or a similar pattern) is incorporated in client-side RIA frameworks. There are only a few client-side frameworks today (for instance, Cairngorn and PureMVC) but I think we’ll see exciting developments in the next year: subscribe to the Gen5 RSS feed to keep up with developments.

]]>int AddToCount(int amount,string countId) {

int countValue=GetCount(countId);

return countValue+amount;

}

This doesn’t work if the GetCount function is asynchronous, where we need to write something like

int AddToCountBegin(int amount,string countId,CountCallback outerCallback) {

GetCountBegin(countId,AddToCountCallback);

}

void AddToCountCallback(int countValue) {

... some code to get the values of amount and outerCallback ...

outerCallback(countValue+amount);

}

Several things change in this example: (i) the AddToCount function gets broken up into two functions: one that does the work before the GetCount invocation, and one that does the work after GetCount completes. (ii) We can’t return a meaningful value from AddToCountCallback, so it needs to ‘return’ a value via a specified callback function. (iii) Finally, the values of outerCallback and amount aren’t automatically shared between the functions, so we need to make sure that they are carried over somehow.

There are three ways of passing context from a function that calls and asynchronous function to the callback function:

- As an argument to the callback function

- As an instance variable of the class of which the callback function is a class

- Via a closure

Let’s talk about these alternatives:

1. Argument to the Callback Function

In this case, a context object is passed to the asynchronous function, which passes the context object to the callback. The advantage here is that there aren’t any constraints on how the callback function is implemented, other than by accepting the context object as a callback. In particular, the callback function can be static. A major disadvantage is that the asynchronous function has to support this: it has to accept a state object which it later passes to the callback function.

The implementation of HttpWebRequest.BeginGetResponse(AsyncCallback a,Object state) in the Silverlight libraries is a nice example. If you wish to pass a context object to the AsyncCallback, you can pass it in the second parameter, state. Your callback function will implement the AsyncCallback delegate, and will get something that implements IAsyncResult as a parameter. The state that you passed into BeginGetResponse will come back in the IAsyncResult.AsyncState property. For example:

class MyHttpContext {

public HttpWebRequest Request;

public SomeObject FirstContextParameter;

public AnotherObject AnotherContextParameter;

}

protected void myHttpCallback(IAsyncResult abstractResult) {

MyHttpContext context = (MyHttpContext) abstractResult.AsyncState;

HttpWebResponse Response=(HttpWebResponse) context.Request.EndGetResponse(abstractResult);

}

public doHttpRequest(...) {

...

MyHttpContext context=new MyHttpContext();

context.Request=Request;

context.FirstContextParameter = ... some value ...;

context.AnotherContextParameter = .. another value ...;

Request.BeginGetResponse();

Request.Callback(myHttpCallback,context);

}

Note that, in this API, the Request object needs to be available in myHttpCallback because myHttpCallbacks get the response by calling the HttpWebResponse.EndGetResponse() method. We could simply pass the Request object in the state parameter, but we’re passing an object we defined, myHttpCallback, because we’d like to carry additional state into myHttpCallback.

Note that the corresponding method for doing XMLHttpRequests in GWT, the use of a RequestBuilder object doesn’t allow using method (1) to pass context information — there is no state parameter. in GWT you need to use method (2) or (3) to pass context at the RequestBuilder or GWT RPC level. You’re free, of course, to use method (1) when you’re chaining asynchronous callbacks: however, method (2) is more natural in Java where, instead of a delegate, you need to pass an object reference to designate a callback function.

2. Instance Variable Of The Callback Function’s Class

Functions (or Methods) are always attached to a class in C# and Java: thus, the state of a callback function can be kept in either static or instance variables of the associated class. I don’t advise using static variables for this, because it’s possible for more than one asynchronous request to be flight at a time: if two request store state in the same variables, you’ll introduce race conditions that will cause a world of pain. (see how race conditions arise in asynchronous communications.)

Method 2 is particularly effective when both the calling and the callback functions are methods of the same class. Using objects whose lifecycle is linked to a single asynchronous request is an effective way to avoid conflicts between requests (see the asynchronous command pattern and asynchronous functions.)

Here’s an example, lifted from the asynchronous functions article:

public class HttpGet : IAsyncFunction<String>

{

private Uri Path;

private CallbackFunction<String> OuterCallback;

private HttpWebRequest Request;

public HttpGet(Uri path)

{

Path = path;

}

public void Execute(CallbackFunction<String> outerCallback)

{

OuterCallback = outerCallback;

try

{

Request = (HttpWebRequest)WebRequest.Create(Path);

Request.Method = "GET";

Request.BeginGetRequestStream(InnerCallback,null);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

OuterCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateError(ex));

}

}

public void InnerCallback(IAsyncResult result)

{

try

{

HttpWebResponse response = (HttpWebResponse) Request.EndGetResponse(result);

TextReader reader = new StreamReader(response.GetResponseStream());

OuterCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateOk(reader.ReadToEnd()));

} catch(Exception ex) {

OuterCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateError(ex));

}

}

}

Note that two pieces of context are being passed into the callback function: an HttpWebRequest object named Request (necessary to get the response) and a CallbackFunction<String> delegate named OuterCallback that receives the return value of the asynchronous function.

Unlike Method 1, Method 2 makes it possible to keep an unlimited number of context variables that are unique to a particular case in a manner that is both typesafe and oblivious to the function being called — you don’t need to cast an Object to something more specific, and you don’t need to create a new class to hold multiple variables that you’d like to pass into the callback function.

Method 2 comes into it’s own when it’s used together with polymorphism, inheritance and initialization patterns such as the factory pattern: if the work done by the requesting and callback methods can be divided into smaller methods, a hierarchy of asynchronous functions or commands can reuse code efficiently.

3. Closures

In both C# and Java, it’s possible for a method defined inside a method to have access to variables in the enclosing method. In C# this is a matter of creating an anonymous delegate, while in Java it’s necessary to create an anonymous class.

Using closures results in the shortest code, if not the most understandable code. In some cases, execution proceeds in a straight downward line through the code — much like a synchronous version of the code. However, people sometimes get confused the indentation, and, more seriously, parameters after the closure definition and code that runs immediately after the request is fired end up in an awkward place (after the definition of the callback function.)

public class HttpGet : IAsyncFunction<String>

{

private Uri Path;

public HttpGet(Uri path)

{

Path = path;

}

public void Execute(CallbackFunction<String> outerCallback)

{

OuterCallback = outerCallback;

try

{

HttpWebRequest request = (HttpWebRequest)WebRequest.Create(Path);

Request.Method = "GET";

Request.BeginGetRequestStream(delegate(IAsyncResult result) {

try {

response = request.EndGetResponse(result);

TextReader reader = new StreamReader(response.GetResponseStream());

outerCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateOk(reader.ReadToEnd()));

} catch(Exception ex) {

outerCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateError(ex));

}

},null); // <--- note parameter value after delegate definition

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

outerCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateError(ex));

}

}

}

The details are different in C# and Java: anonymous classes in Java can access local, static and instance variables from the enclosing context that are declared final — this makes it impossible for variables to be stomped on while an asynchronous request is in flight. C# closures, on the other hand, can access only local variables: most of the time this prevents asynchronous requests from interfering with one another, unless a single method fires multiple asynchronous requests, in which case counter-intuitive things can happen.

Conclusion

In addition to receiving return value(s), callback functions need to know something about the context they run in: to write reliable applications, you need to be conscious of where this information is; better yet, a strategy for where you’re going to put it. Closures, created with anonymous delegates (C#) or classes (Java) produce the shortest code, but not necessarily the clearest. Passing context in an argument to the callback function requires the cooperation of the called function, but it makes few demands on the calling and callback functions: the calling and callback functions can both be static. When a single object contains both calling and callback functions, context can be shared in a straightforward and typesafe manner; and when the calling and callback functions can be broken into smaller functions, opportunities for efficient code reuse abound.

]]>There’s a lot of confusion about how asynchronous communication works in RIA’s such as Silverlight, GWT and Javascript. When I start talking about the problems of concurrency control, many people tell me that there aren’t any concurrency problems since everything runs in a single thread. [1]

It’s important to understand the basics of what is going on when you’re writing asynchronous code, so I’ve put together a simple example to show how execution works in RIA’s and how race conditions are possible. This example applies to Javascript, Silverlight, GWT and Flex, as well as a number of other environments based on Javascript. This example doesn’t represent best practices, but rather what can happen when you’re not using a proactive strategy that eliminates concurrency problems:

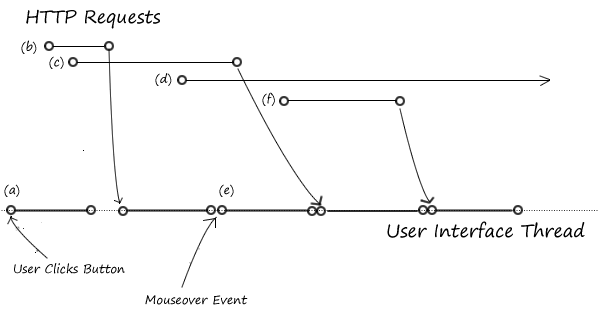

In the diagram above, execution starts when the user pushes a button (a). This starts the user interface thread by invoking an onClick handler. The user interface thread starts two XmlHttpRequests, (b) and (c). The event handler eventually returns, so execution stops in the user interface thread.

In the meantime, the browser still has two XmlHttpRequests running. Callbacks from http requests, timers and user interfaces go into a queue — they get executed right away if the user interface thread is doing nothing, but get delayed if the user interface thread is active.

Http request (b) completes first, causing the http callback for request (b) to start. Had something been a little different with the web browser, web server or network, request (c) could have returned first, causing the callback for request (c) to start. If the result of the program depends on the order that the callbacks for (b) and (c) run, we have a race condition. The callback for http request (b) starts a new http request (d), which runs for a long time.

In the meantime, the user is moving the mouse and triggers a mouseover event while the request (b) callback is running. Right after the request (b) callback completes, the web browser starts the UI thread, which causes a mouseover event handler (e) to run. Note that the user can trigger user interface events while XmlHttpRequests are running, causing event handlers to run in an unpredictable order: if this causes your program to malfunction, your program has a bug.

While the event handler (e) is running, request (c) completes: like the mouseover event, this event is queued and runs once event handler (e) completes. Before (e) completes, it starts a new http request (f). The browser looks into the event queue when (e) completes, and starts the callback for (c). Http request (f) completes while callback (c) is running, gets queued, and runs after (c) is running.

At the end of this example, the callback for (f) completes, causing the UI thread to stop. The http request (c) is still in flight — it completes in the future, somewhere off the end of the page.

This example did not include any timers, or any mechanism of deferred execution such as DeferredCommand in GWT or Dispatcher.Invoke() in Silverlight. This is but another mechanism to add callback references to the event queue.

As you can see, there’s a lot of room for mischief: http requests can return in an arbitrary order and users can initiate events at arbitrary times. The order that things happen in can depend on the browser, it’s settings, on the behavior of the server, and everything in between. Some users might use the application in a way that avoids certain problems (they’ll think it’s wonderful) and others might consistently or occasionally trigger an event that causes catastrophe. These kind of bugs can be highly difficult to reproduce and repair.

Asynchronous RIAs have problems with race conditions that are similar to threaded applications, but not exactly the same. Today’s languages and platforms have excellent and well documented mechanisms for dealing with threads, but today’s RIAs do not have mature mechanisms for dealing with concurrency. Over time we’ll see libraries and frameworks that help, but asynchronous safety isn’t something that can be applied like deodorant: it involves non local interactions between distant parts of the program. The simplest applications can dodge the bullet, but applications beyond a certain level of complexity require an understanding of asynchronous execution and the consistent use of patterns that avoid trouble.

[1] Although it is possible to create new threads in Silverlight, all communication and user interface access must be done from the user interface thread — many Silverlight applications are single-threaded, and adding multiple threads complicates the issue.

]]>Minimizing Code Paths In Asynchronous Code, a recent post of his, is about a lesson that I learned the hard way with GWT that applies to all RIA systems that use asynchronous calls. His example is the same case I encountered, where a function might return a value from a cache or might query the server to get the value: an obvious way to do this in psuedocode is:

function getData(...arguments...,callback) {

if (... data in cache...) {

callback(...cached data...);

}

cacheCallback=anonymousFunction(...return value...) {

... store value in cache...

callback(...cached data...);

}

getDataFromServer(...arguments...,cacheCallback)

}

At first glance this code looks innocuous, but there’s a major difference between what happens in the cached and uncached case. In the cached case, the callback() function gets called before getData() returns — in the uncached case, the opposite happens. What happens in this function has a global impact on the execution of the program, opening up two code paths that complicate concurrency control and introduce bugs that can be frustrating to debug.

This function can be made more reliable if it schedules callback() to run after the thread it is running in completes. In Javascript, this can be done with setTimeout(). In Silverlight use System.Windows.Threading.Dispatcher. to schedule the callback to run in the UI thread.

]]> void CallingMethod(...) {

... do some things ...

IAsyncFunction<String> httpGet=new HttpGet(... parameters...);

anAsynchronousFunction.Execute(CallbackMethod);

}

void CallbackMethod(CallbackReturnValue<String> crv) {

if (crv.Error!=null) { ... handle Error, which is an Exception ...}

String returnValue=crv.Value;

... do something with the return value ...

}

We’re using generics so that return values can be passed back in a type safe manner. The type of the return value of the asynchronous function is specified in the type parameter of IAsyncFunction and CallbackReturnValue.

Asynchronous functions catch exceptions and pass them back in in the CallbackReturnValue. This makes it possible to propagate exceptions back to the caller, as in synchronous functions. The code to do this must has to be manually replicated in each asynchronous function, however, the code can be put into a wrapper delegate.

You could do the same thing in Java, but the CallbackMethod would need to be a class that implements an interface rather than a delegate.

In C# it takes one class, one interface and one delegate to make this work:

public delegate void CallbackFunction<ReturnType>(CallbackReturnValue<ReturnType> value);

public class CallbackReturnValue<ReturnType> {

public ReturnType Value {get; private set; }

public Exception Error {get; private set; }

protected CallbackReturnValue() { }

public static CallbackReturnValue<ReturnType> CreateOk(ReturnType value) {

CallbackReturnValue<ReturnType> crv=new CallbackReturnValue<ReturnType>();

crv.Value=value;

return crv;

}

public static CallbackReturnValue<ReturnType> CreateError(Exception error) {

CallbackReturnValue<ReturnType> crv = new CallbackReturnValue<ReturnType>();

crv.Error = error;

return crv;

}

}

public interface IAsyncFunction<ReturnType>

{

void Execute(CallbackFunction<ReturnType> callback);

}

Here’s a simple example of an asynchronous function implementation:

public class HttpGet : IAsyncFunction<String>

{

private Uri Path;

private CallbackFunction<String> OuterCallback;

private HttpWebRequest Request;

public HttpGet(Uri path)

{

Path = path;

}

public void Execute(CallbackFunction<String> outerCallback)

{

OuterCallback = outerCallback;

try

{

HttpWebRequest Request = (HttpWebRequest)WebRequest.Create(Path);

Request.Method = "GET";

Request.BeginGetRequestStream(InnerCallback,null);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

OuterCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateError(ex));

}

}

public void InnerCallback(IAsyncResult result)

{

try

{

HttpWebResponse response = (HttpWebResponse) Request.EndGetResponse(result);

TextReader reader = new StreamReader(response.GetResponseStream());

OuterCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateOk(reader.ReadToEnd()));

} catch(Exception ex) {

OuterCallback(CallbackReturnValue<String>.CreateError(ex));

}

}

}

Asynchronous Functions provide a simple and typesafe way to build asynchronous functions by composing them out of simpler asynchronous functions, and it provides a reasonable way to emulate the usual bubbling of exceptions that allows callers to catch exceptions thrown inside a callee. (Without this kind of intervention, exceptions in the callback functions propagate in the reverse of the usual direction!) Over the next few posts, we’ll talk about how asynchronous execution really works, which is essential for getting good results with Asynchronous Functions.

]]>public class MyPanel:StackPanel {

... other functions ...

void SubmitButton_Click(Object sender,EventArgs e) {

... collect data from forms ...

ServerWrapper.DoSubmission(formData,SubmissionCallback);

}

void SubmissionCallback(SubmissionResult result) {

... update user interface ...

}

}

(Although code samples are in C#, the language I’m using now, I developed this pattern when working on a Java project.) This is a straightforward pattern for the simplest applications, but it runs out of steam when your application becomes more complex. It can become confusing to keep track of your callback functions when your object does more than one kind of asynchronous call: for instance, if it has multiple buttons. If the same action can be done on the server from more than one place in the UI, it’s not clear where the callback belongs.

One answer to the problem is to use the Command Pattern, to organize asynchronous activities into their own classes that contain both the code that initiates an asynchronous request and the callback that runs when the request completes.

The Command Pattern turns a verb into a noun — it turns a method into an object. Commands implement an interface like

public interface ICommand {

void Execute();

}

The parameters of a Command can be set in it’s constructor, or can be set by setting properties on the Command — setting parameters in the constructor is less error prone, although when you’ve got twenty or so optional parameters, it’s a lot easier to use properties. In this case, we’ll organize the code like so

public class SubmitFormCommand:ICommand {

private FormData Data;

public SubmitFormCommand(FormData data) {

Data=data;

}

public void Execute() {

... processing ...

ServerWrapper.DoSubmission(Data,Callback);

}

public void Callback(SubmissionResult result) {

... update user interface ...

}

}

The code in the Click handler now looks like this:

void SubmitButton_Click(Object sender,EventArgs e) {

... collect data from forms ...

ICommand action=new SubmitFormCommand(formData);

action.Execute()

}

It makes sense to demarcate Commands so that they can be obviously distinguished from other classes: I like to always have ‘Command’ at the end of the class name and I like to keep them in a subdirectory titled ‘Commands’.

Note that I’m assuming that updating of the UI isn’t tightly coupled to the object which is executing the command, otherwise I’d want the command to pass notification back to the calling object via a callback or event (which is the subject of the next article.) Rather, I’m imaging that the application is complex enough that multiple UI elements may need to be updated when the result comes back — in a case like that, UI update code doesn’t logically belong to the UI element that initiates the action. Although it’s possible to hardcode notification logic in the Command, it’s probably best to construct some kind of publish/subscribe notification system that passes updates to UI elements that are affected by changes to data items.

It’s also a bit simplistic to simply use an interface here: one of the great things about the Command pattern is that a Command (unlike an ordinary method) can be broken down into pieces which can be implemented or overridden in subclasses. I’ll often implement an abstract class like so:

public class AsyncCommand:ICommand {

protected abstract void DoWork();

public Execute() {

... do some actions common to all commands ...

DoWork();

}

}

This works a bit like Aspect Oriented Programming and is good for logging, concurrency control and many other purposes. It’s also possible (and desirable) to wrap your callback methods, although (in mainstream languages) that does require you to write them a certain way — I’ll be talking about that in future posts.

]]>For instance, suppose that you’re doing a search, and then you’re displaying the result of the search. The most reliable way to do this is to use Pattern Zero, which is, do a single request to the server that retrieves all the information — in that case you don’t need to worry about what happens if, out of 20 HTTP requests, one fails.

Sometimes you can’t redesign the client-server protocol, or you’d like to take advantage of caching, in which case you might do something like this (in psuedo code):

getAListOfResults(new AsyncCallback {

... clearGUI();

foreach(result as item) {

fetchItem(item,new AsyncCallback {

... addItemToGui()

}

}

First we retrieve a list of items, then we retrieve information about each item: this is straightforward, but not always reliable. Even if your application runs in a single thread, as it would in GWT or if you did everything in the UI thread in Silverlight, you can still have race conditions: for instance, results can come back in a random order, and getAListOfResults() can be called more than once by multiple callbacks — that’s really the worst of the problems, because it can cause results to appear more than once in the GUI.

There are a number of solutions to this problem, and a number of non-solutions. A simple solution is to make sure that getAListOfResults() never gets called until the result set has come back. I was able to do that for quite a while last summer, but the application finally reached a level of complexity where it was impossible… or would have required a major redesign of the app. Another is to use pessimistic locking: to not let getAListOfResults() run while result sets are coming back — I think this can be made to work, but if you’re not careful, your app can display stale data or permanently lock up.

Fortunately there’s a pattern to retrieve result sets using optimistic locking that displays fresh data and can’t fail catastrophically

class Whatever {

int transactionId=0;

public updateGUI() {

getAListOfResults(new AsyncCallback {

transactionId++;

final int currentTransactionId=transactionId;

... clearGUI();

foreach(result as item) {

fetchItem(item,new AsyncCallback {

if (transactionId != currentTransactionId)

return

... addItemToGui()

}

}

}

The gist of this is that each result set is assigned a unique transaction id — once the list of items comes back, we clear the GUI, then we ignore fetchItem() callbacks from prior transaction id’s. In a multi-threaded environment, you’ll need to take care that transactionId’s are generated atomically.

Let’s think about how this algorithm holds up in the face of failure: suppose one of the fetchItem() calls fails to return. Perhaps the callback is going to come back with a failure code, but you never know. (It certainly doesn’t in some off-brand browsers with GWT) A pessimistic locking scheme would require some way of knowing when the request is done — it would have to count all the fetchItem() calls that return… If one doesn’t come back, the application could be locked up forever. You could try to fight this by setting a timeout, but getting correct behavior in every strange case could be a lot of work.

The code above might not always do the correct thing, but it always does something sane. If one of the fetchItem() call fails, the item will fail to appear in the list. If the failure is a transient failure, you could say this is a fault of the algorithm: this could be patched over by retrying the failed request. If, on the other hand, the failure is the fault of the server (say the fetchItem() call crashes with a particular argument) this algorithm keeps the client app available.

Note that another detail is missing from this code sample: fetchItem() callbacks can come back in a random order, so that the order that items appear in the GUI is not guaranteed. In some cases you might not care. If you do care, you can associate a sequenceNumber with each fetchItem() request (for instance, using a closure as we do with the currentTransactionId) and then use the sequenceNumber to place each item in the right place in the GUI.

The Optimistic Locking pattern is a simple and provably reliable solution to the problem of retrieving detailed information about items in a result set — in particular, it’s immune to catastrophic failures that can befall pessimistic locking schemes. Many people have proposed solutions to this problem that work sometimes, but not always: you don’t want to waste your time chasing Heisenbugs… Start with reliable patterns and build from there.

]]>